Henrietta Collier-Johns

George Caleb (G.C.) Collier was the wealthy white land owner who founded the Town of Brundidge, Alabama, in the mid 1800’s. It was not uncommon for slave owners to engage in sexual congress with their servants , and G.C. Collier was no exception. Collier’s slave mistress was Sally McGuire, and Sally gave birth to a very light skinned daughter who was named Henrietta. It was well known that Henrietta was fathered by G.C. Collier, and Henrietta was given a station in life unlike that of any other children of Collier’s servants. Henrietta was very well educated, dressed finely, and taken care of with means that far exceeded that available to typical black servant families in Brundidge.

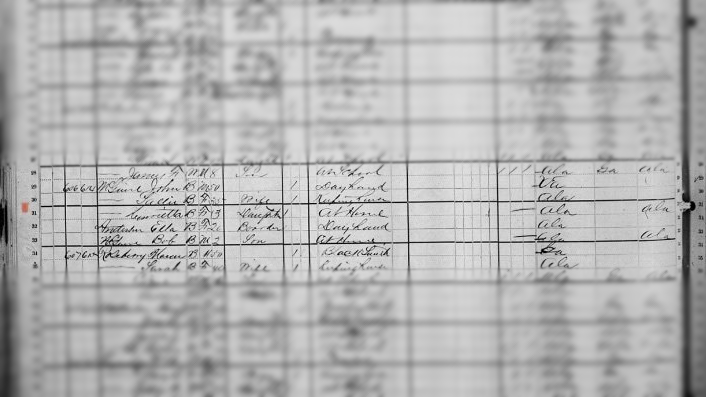

The earliest official record we have of Henrietta is an 1880 census which shows a 3 year old Henrietta living with her mother Sally (who was 35 years old at the time) and her father listed as John McGuire, a 50 year old black “day hand” who certainly did not sire light skinned progeny such as Henrietta, and would not have, at a day hand’s wages, had the means by which to provide for Henrietta in the manner that the photographs clearly show that she was accustom to living.

1880 Census

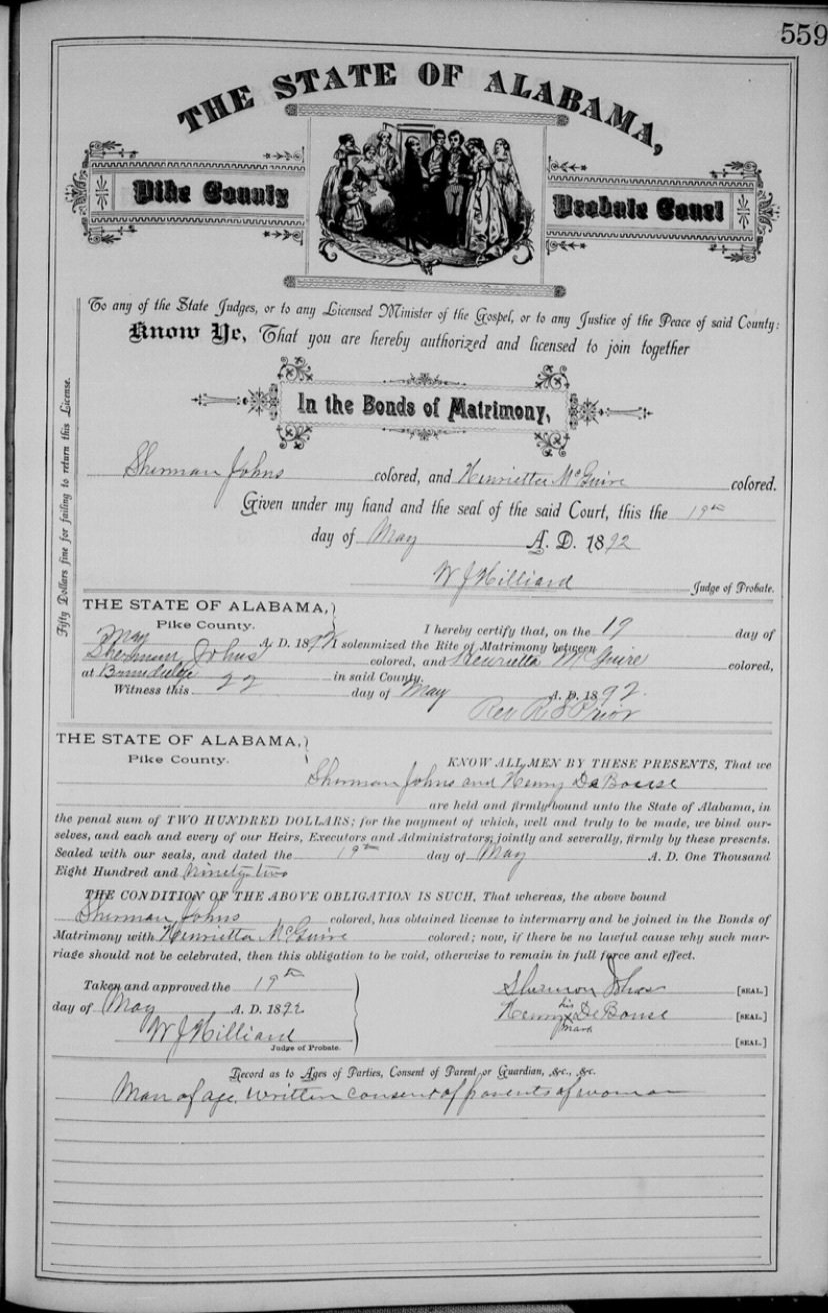

The Marriage of Henrietta

G.C Collier died in 1891, and while his estate was being probated by T.A. Collier (George’s older brother), Henrietta was married to Sherman Johns. Sherman came from a well known Creek Indian family from Coffee County. As the rights of mulatto women to inherit property from white land owners would have been a new, practically unheard of, and precariously fragile concept — especially given that the deep antebellum South that had just lost the the Civil War and was not particularly known for upholding the rights of black citizens — this maneuver was most likely undertaken to help protect Henrietta’s interest in the Collier estate from the white farmers that wanted to try to reclaim land that Collier had lawfully seized after the farmers defaulted on their farm loans. Henrietta’s inheritance from Collier was much less likely to be challenged by the white farmers if she had influential relatives through her husband Sherman.

Henrietta’s Marriage Certificate

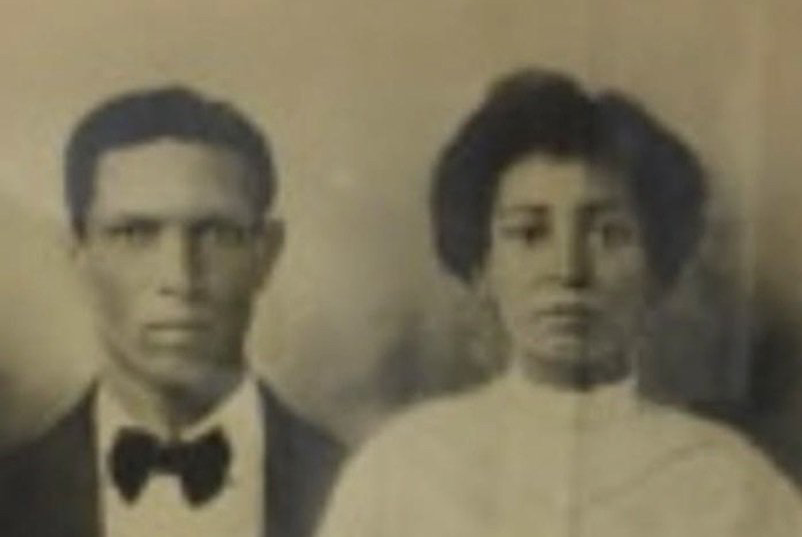

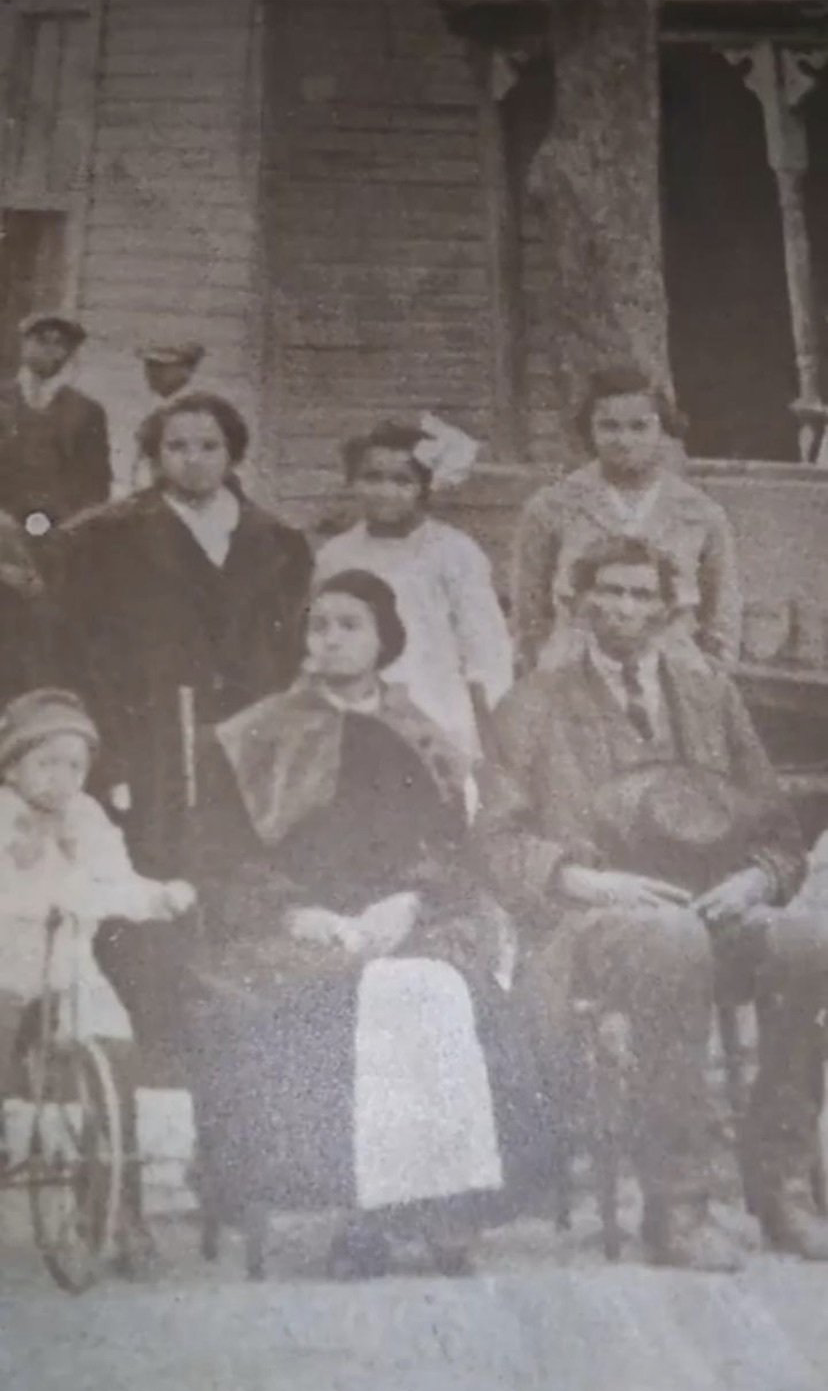

This picture of Henrietta and Sherman was taken in the early 1890’s soon after they were married

Johns Family Photograph‘s (circa 1917)

C.W. Johns (on left)(Charles’ Grandfather)

Henrietta & Sherman Johns (seated)

Johns’ Family Properties & Businesses

As Charles was growing up, the older black towns people, who were living in Brundidge at the time before his family was banished by the KKK, told him that his family owned land “as far as you can see..... and then as far as you could see after that” (Mr. Clem Pugh); how they would work in the Johns family’s cotton fields and at the Johns’ cotton gin from “sunup to sundown” (Ms. Mae Lou Brown - member of the Order of the Eastern Star (OES)); and that “it is a shame what they did to your family... they were ‘run out of town’ by the Klu Klux Klan... we woke up the next day and the white people claimed they now owned everything” (Ms. Casey Frazier - member of the OES). You can listen to Charles tell you himself how these older black towns people wanted to be sure to pass on to him that they had been a part of something that the white people of the town were trying to erase, and that they wanted the black history to be remembered. See our You Tube video (below) where Charles describes his family’s battle to get their property title documents from the Pike County Probate Court. In this video Charles describes how these black towns people would make it a point to be sure he knew what they had seen, experienced, and participated in. They knew they had bore witness to a very special chapter of black history, when a black family had been successful and thriving in the deep South, before it was all taken away from them by the KKK and the white families jealous of the Johns family’s prosperity.

<https://YouTu.be/xiDy60YVkPc>

Click Below

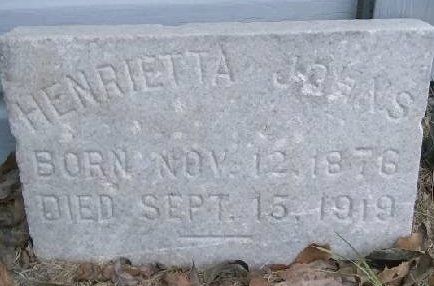

Henrietta’s Death

In 1919, only two years after the group family photograph was taken, Henrietta died under very mysterious circumstances, and was most likely murdered or lynched by the Klu Klux Klan and their sympathizers in Brundidge. When Charles was only 10 years old, he was looking at the family photographs, to include the one of Henrietta, and asked his grandfather, C.W. Johns (the light skinned young man in the picture above with his leg up on the bumper of the Model T), how his mother, Henrietta, had died. It was an innocent enough question for a 10 year old child curious about the family members he was seeing in the pictures at his grandfather’s house. It was his grandfather’s reaction, however, that shocked Charles, as he had never seen an adult act that way before. His grandfather, C.W., was normally a very calm, stoic man who was unflusterable, always immaculately dress, and ran a small general store in Brundidge. When Charles asked about Henrietta’s death, this normally reserved man become quite visibly upset and started shaking uncontrollably. This continued until C.W. was able to get ahold of the family Bible, started reading it softly to himself. Eventually C.W. gradually began to calm down and stopped shaking. He never answered Charles’ question and, based upon the strong reaction he had witnessed, Charles was afraid to ask any more about it. Normally, if someone dies of natural causes, or of some tragic misfortune or accident, the story gets told and the family moves on from the incident. When someone dies in a terribly violent way, in a manner meant to strike fear into the family members that remain, then the story would not necessarily get told lest the fear imparted to one generation gets passed on to the next. It is quite obvious that C.W. wanted to protect his grandson, Charles, from the fear and suffering C.W. had experienced when Henrietta died. Henrietta’s body was never recovered and, in lieu of a grave, C.W. placed a memorial stone at his general store which honored the memory of his mother. The placing of Henrietta’s stone in such a public place, where everyone walking down the street, white or black, would be reminded of her life & death, was a significant act of defiance against those who were responsible for his mother’s disappearance and the attempt to erase her from the historical record. In the 1980’s, when Charles and his brother were carefully removing the memorial stone from the dilapidated wreckage of the store, they found six dimes placed underneath it. All of these dimes were dated 1919, the year that Henrietta died, and would have been placed there by her six children.

It is no coincidence that Henrietta mysteriously “disappeared”on September 25, 1919, as this was during the period known as the “Red Summer” (from April to November, 1919) when the Klu Klux Klan was experiencing their biggest resurgence in popularity and was responsible for carrying out dozens of lynchings and banishments across the South. This was no poor black woman that they were murdering, but someone who had social standing in the community. Someone of that stature in society does not just mysteriously go “missing” unexplainably from the community in which she lives. Her killing would not have been the usual semi- public spectacle carried out by unnamed assailants, and her body left on display to send a message to other black townspeople; Henrietta’s killing was a much more clandestine affair, and meant to strike fear into the hearts of the Johns family.

Henrietta’s Stone

Henrietta’s Paternal Surname

On the official census and marriage certificates (above), Henrietta’s paternal surname is listed as “McGuire” which is the name of the man her mother Sallie lived with, John Mcguire. In the 1880 census McGuire reported that his birthplace was Virginia and, given that blacks slaves in the South could not freely travel, it was most likely that he was brought to Alabama by the Colliers as a servant. The last census to report black servants as “slaves” was in 1860, and in 1880 it was common to list a servant’s occupation as a “day hand” if the man’s work was performed outside on the farm or plantation that the white family owned. As a “day hand” (see census, above) John Mcguire would certainly not have had the means by which to provide Henrietta the education, the clothing, or the elevated standard of living with which she was obviously quite familiar. Her pictures show that she was clearly not the daughter of a ‘day hand’ servant. It is also not surprising that official documents did not list her paternal surname as “Collier” since mulatto children born of an illicit relationship between a white land owner and a slave mistress would not have been officially acknowledged, especially in the Deep South. But people back then, white or black, were not ignorant of the secret liaisons that occurred between former masters & servants - no matter how taboo such relationships were considered at the time. Everyone knew that Sallie’s extremely light skinned daughter, Henrietta, was fathered by G.C. Collier, and not by the older black day hand, John Mcguire. This is further corroborated by the transfer of Collier’s estate properties to Henrietta at some point after Collier’s death. In 1982, after his grandfather C.W. Johns had passed away, Charles asked his grandmother, Mittie Johns, “What was granddaddy’s momma’s name?” Mittie Johns, a quiet, reserved, and pious woman whom Charles had never heard speak in a harsh tone to anyone, actually raised her voice in anger and told Charles “Her name was Henrietta Collier, and don’t you ever forget it!” Just as with his grandfather’s reaction when 10 year old Charles had asked about how Henrietta had died, this reaction by his grandmother made a lasting impression upon Charles.